On the Subject of Authenticating Works by Franz West

Download as PDFContents

2. On Franz West’s concept of artwork and authorship

2.1 “What is an author?”: West’s participation in a postmodern discourse

2.2 Passstücke (“Adaptives”)

2.3 Furniture

2.4 Sculptures

2.4.1 Outdoor sculptures made of metal and epoxy resin

2.5 Works on paper and cardboard

2.5.1 Ironizing promises of happiness

2.5.2 Comments on the art industry, Signaturalismen (“Signaturalisms”)

2.5.3 The reception of art as a subject in West’s works on paper and cardboard

2.6 Picture walls, installations

2.6.1 Integration of works by other artists

2.7 Summary and conclusions

2.7.1 On West’s integration of fakes into his own creative work

3. On the topic of fakes in the style of Franz West’s works

3.1 Point of departure: Documenting West’s oeuvre

3.2 First indications of fakes

3.3 Notification of and investigations by the police

3.4 Investigations by the Archiv Franz West (AFW)

3.5 The suspicious collector and his version of the story

3.6 Authenticity sheets (ABC assessments)

3.7 Decisions left untaken

3.8 Accusations and defamation of Franz West

3.9 West’s published statement on the fakes

4. Authentication after Franz West’s death

4.1 Continued research

4.2 Authentication criteria, statements by the artist

4.3 Afterword

1. The basics

It is one of the tasks of every artist’s archive to answer questions regarding the authenticity of works associated with the artist’s name. The Archiv Franz West (AFW) also complies with this duty, though in the case of this artist that presents a particular challenge.

First and foremost this is due to the artist’s self-doubts regarding the quality of his creative output—something that is common to numerous artists but that was especially pronounced with Franz West. For that reason, it was not always easy for him to say whether a piece was indeed his work, and he was also known to change his mind. The AFW therefore sees it as its responsibility to check the authenticity of works in line with numerous other criteria in addition to the answers given by the artist.

To this is added West’s specific understanding of the concept of artwork and authorship that enabled him to integrate works by other creators into his own oeuvre, which in some cases also involved incorporating fakes. Therefore, a particularly nuanced approach is needed when considering issues of authenticity concerning works attributed to Franz West, which must be based on a nuanced understanding of his concept of artwork and authorship. Consequently, this topic will form the starting point of this essay, which will then go on to explore the subject of fakes of is works.

2.1 “What is an author?”: West’s participation in a postmodern discourse

Reflecting on the concept of art and authorship is a key aspect of the oeuvre of Franz West. In doing so, he was taking part in a discourse that grew in importance from the 1960s.

After a long history of varying, superseding notions and definitions of what constitutes art, the conviction increasingly took hold that an unequivocal and above all conclusive answer to this question is not possible. At different times and in different contexts, as well as depending on the respective author, art has always defined itself differently and served different functions. This insight logically led to reflections on what constitutes an author and furthermore, to what extent they can define not only the respective concept of art but also the impact and meaning of their creations. In turn, the latter draws our attention to the recipients and their role in the creation of meaning.

It is not for no reason that these questions were raised in the so-called “postmodern” discourse (post-1960), a time when people started questioning the certainties and postulates of High Modernism. Whereas the latter had celebrated artist-heroes as the givers of meaning to their creations and restricted the role of the audience to that of viewers, a change in thinking was now underway. Key texts in this regard were written by Umberto Eco (The Open Work, 1962, trans. 1989), Roland Barthes (The Death of the Author, 1967, trans. 1967), and Michel Foucault (What Is an Author?, 1969, trans. 1998). Coming from the field of semiotics or literature and philosophy, these authors triggered a paradigm shift that led to the act of producing impact and meaning being assigned to a much greater degree than ever before to the recipient and less to the creator of a work.

This reversal or at least shift or reallocation of the process of giving meaning assigned a different role not only to the audience but also to the work of art. It is no longer the carrier or emanator of meaning per se, but rather the trigger of experiences in its recipients—experiences that will vary with each person, giving rise to ever-new and different meanings.

This notion has increasingly come to define both the approach of many artists and the discourse about art since the last third of the twentieth century. It endorses participative approaches, i.e., works that require (or at least encourage) the audience to actively interact with the piece, be it the experience of spatial settings or even physically handling objects. With this new function of a work of art, the creative achievement of the individual or genius artist is also (somewhat) removed from the limelight and the work deprived of any claim to an aura. Among other things, this leads to more un-auratic forms of presentation, like works being positioned close together on picture walls or in spatial installations, or unframed works simply being pinned to the wall, an approach that evens out the importance of each individual creation and declares its respective content, i.e., its statement, potential impact, and meaning, as always only one among many possibilities.

All these criteria certainly hold true for the approach of Franz West. His works contradict the cult of the author, indeed they express an explicit statement against High Modernism’s concept of a heroic genius with (predominantly male) star artists, who in their respective cases very precisely defined what constitutes art and how it—i.e., their own creations!—should be received.

He countered this with an art that neither celebrates its author nor offers guidelines as to its reception. Instead, his works are always triggers, starting points for the audience’s own experiences, reflections, or interpretations, precisely in the sense of Barthes’s conviction (formulated in the field of literature) that it is not the author (alone), but to a great extent the readers who produce meaning, which is always different in repeated readings. West even explicitly understood the recipients’ reactions as integral components of the work. It is only in dialogue with a recipient that his works fulfill their function; the artist’s creation is merely one part that needs another.

The dialogue with his works that West intended can take place on the physical, psychological, mental, and intellectual level.

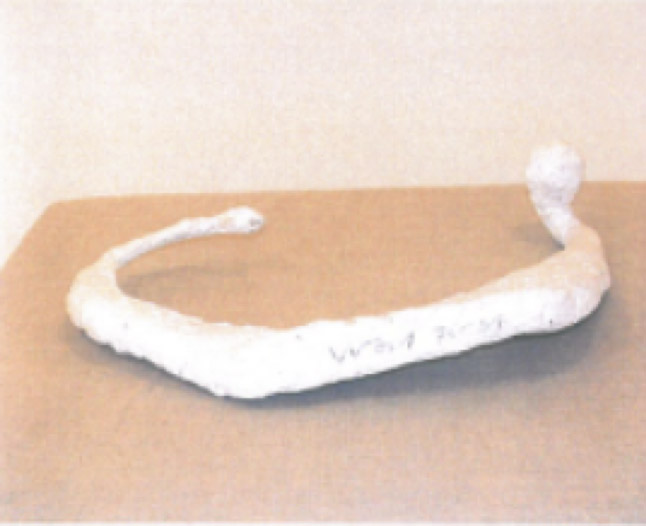

2.2 Passstücke (“Adaptives”)2

From 1974 onward West created Passstücke (“Adaptives”)—sculptural entities with which the recipients may primarily interact on a physical level without any guidelines and entirely as they wish. Nothing should be imposed on anyone. The art object here is the starting point and stimulus for experiences, a tool with which to produce and perceive situations and the Befindlichkeiten (states of being)3 associated with them. It was one of West’s basic convictions that the latter are to a substantial extent defined by the objects with which we come into contact, just as they are by the settings and contexts in which we move and therefore are in constant flux. However, West considered the experience of the various states of being as the only manner in which we may take in the world—and hence took a stance against postulates according to which a superindividual “being” can be experienced.

2.3 Furniture

West’s pieces of furniture are developed out of the Passstücke (“Adaptives”) concept in the sense that they are also objects with which the body comes into direct physical contact. They, too, may be used according to every person’s individual choice, even though the options are more limited than with the Passstücke and the free choice of location is less easy to accomplish. Yet their use (different in each case) in various settings and at various times influences the respective state of being (different in each case) of each person—and hence their respective experience (different in each case) of the world.

Furthermore, West’s furniture sculptures offer sites for dialogue between their recipients.

2.4 Sculptures

In addition to the Passstücke (“Adaptives”) and pieces of furniture that invite physical interaction, West also created sculptures from the 1980s with which dialogue can only take place on the mental and/or intellectual level.

An early example are the Reflektoren (“Reflectors”), a less well-known group of works from the first half of the 1980s: relatively small sculptural formations (generally painted by other artists) that may serve as starting points for a conversation, as an accompanying text on slips of paper supplied by the artist explains. Very easy to transport, these pieces can be laid on the table of a coffeehouse, for example, to strike up a conversation.

From the mid-1980s, so-called “legitimate sculptures” (as West called them in an initial exhibition in 1986) emerged, which were intended neither for physical use nor for transport by their recipients, but rather are positioned statically (at times even on pedestals).

But these, too, were conceived by West not as autonomous works for mere contemplative viewing or as pieces whose inherent message was to be deciphered. Rather, they were again intended to trigger individual experiences and readings and hence ever-new dialogues with the object. Stimuli for this are offered by the works’ informal qualities, which are particularly well suited to prompting associations (with West keenly playing with the tendency to physiognomize). Added to this are linguistic accompaniments. They may be titles, but very often also texts considered integral parts of the works. At times quite cryptic, these are placed alongside the sculptures in various forms in order to stimulate a dialogue with the audience.

2.4.1 Outdoor sculptures made of metal and epoxy resin

The large outdoor sculptures made of metal or epoxy resin can be described as being between sculpture and furniture. They are likewise characterized by forms particularly apt to inviting associations though their formal repertoire is not the informal, but rather elementary (but never exact!) stereometric forms, including egg shapes and spheres as well as “Wuuste,” sausage-like shapes that might also be entangled or knotted. Once again, in many cases there are linguistic accompaniments that trigger associations. Furthermore, some of these sculptures can serve as seating and thus be used physically like West’s Passstücke (“Adaptives”) or furniture.

2.5 Works on paper and cardboard

West’s conviction that the experience of any state of being can be the only possible and constantly changing mode of perceiving the world and that this is to a considerable extent defined by our interaction with objects and surroundings, also underlies his works on paper. Here, on the one hand states of being are created and on the other hand (cynical) comments are voiced on the promises of happiness made by the worlds of media and advertising.

Another important subject in this group of works is the question present throughout West’s oeuvre of what an artwork is or is capable of and what constitutes an artist.

2.5.1 Ironizing promises of happiness

Even West’s earliest drawings and watercolors (from the period between 1970 and 1973) predominantly show the occasional person who, inactive and solitary, quite simply “finds themselves” in (often enigmatic) situations and in places of longing.

Around 1974, at roughly the same time he started the Passstücke (“Adaptives”), a series of works was begun that also offers triggers for the recipients’ own experiences. It confronts us with monochrome surfaces (partly structured with various incorporated materials) in the somber colors that defined the reality of West’s life in 1970s Vienna and affect one’s state of mind, like “government office green,” or the “poo brown” in which many doors were painted at that time. Occasionally, the kind of “cute stickers” are applied to such surfaces that in those days were affixed to various places in living areas or on everyday objects to counter the dreariness with a “cheerful mood.”

This series was followed by the sheets of the 1970s on which West satirized or viewed skeptically and critically the promises of happiness made by the world of consumption by overworking magazine pages or direct mail showing “happy” people or tantalizing consumer goods with paint or colored paper. This includes sheets that tackle the “pleasures” of sexuality. It is not without humor that West relativizes—indeed derides—all these promises of happiness by isolating and thus “showing up” the subjects. With his interventions he partly changes them or exposes them to ridicule by garnishing and hence exaggerating them. In addition, he occasionally wrote sardonic comments on them.

A humorously subversive comment on the (alleged) delights of hypersexuality is also the subject of a series of sheets Im Aktionismusgeschmack (“In the Actionist taste”). Here West explicitly makes reference to Otto Muehl and his commune in which free sexuality was practiced. By taking to the ridiculous the latter’s obsession with sex (and other violations of taboos like urinating in front of people), his importance is simultaneously relativized. Muehl was an insider hero of the Viennese art world at the time and already prominent as an enfant terrible due to his scandalized actions, styling himself as a genius and guru.

2.5.2 Comments on the art industry, Signaturalismen (“Signaturalisms”)

The question what art is and how it defines itself, and hence also what constitutes an artist, or rather who is successful in this area and for what reason, pervades West’s entire oeuvre.

As early as 1972 he depicts the then heroes of the Viennese art world—drawn schematically as was his style at the time—with their names written underneath. In later sheets from the 1970s, only the artists’ names are written on the picture.

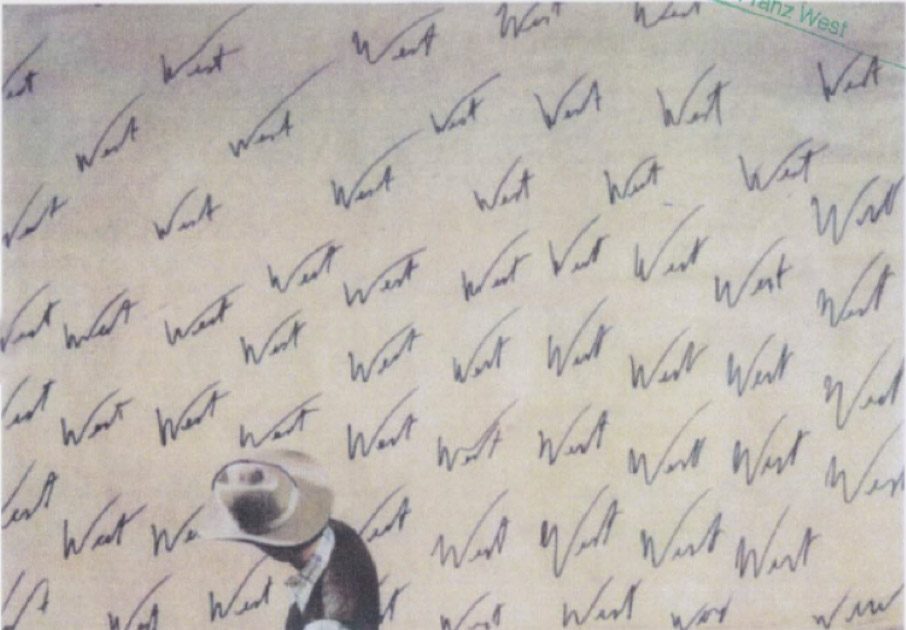

Such works were followed by the so-called Signaturalismen (“Signaturalisms”), sheets on which West “collected” the autographs of celebrities in the art world. These works were in fact about much more, as they address the issue of signatures, which even if not entirely accounting for a work’s price, certainly raise it, and also tackle the concept of authenticity—something that is extremely important in relation to the subject of fakes.5

West “played” with his own signature throughout his life. He changed it numerous times: both the name itself—which he changed from Zokan, his father’s name, to West, his mother’s maiden name—and the writing style, which varied significantly, including decidedly mannered variants. Added to this are unconventional wordings in his signatures, such as “Made by FW,” as a cynically subversive comment on the monetary value of art.

Of particular interest is a sheet on which his name is repeated in regular intervals to fill the picture plane. Here his name is not a signature but a subject and tool with which he claims belonging to the league of famous artists. At the same time, it may be read as a humorous, tongue-in-cheek, over-affirmation of authenticity whose relevance for the artwork and its possible impacts he has here put at stake.

West himself left many of his overworkings of newspaper pages from the 1970s unsigned—in his words “out of principle.”6

His sheets Im Aktionismusgeschmack (“In the Actionist taste”) are signed, but here he “played” with the dates. For example, they may say 1976–74—i.e., with the dates inverted—which begs the question whether he really did work on these sheets for two years. In fact, it is probably more likely that he was deliberately trying to cause confusion; a subversive comment on and thwarting of the tools used by the art industry to bestow authority, meaning, value, and not least authenticity (!), which he counters just like the promises and values of the worlds of consumption and the media.

When in later years he was repeatedly asked (or indeed in many cases urged!) to sign earlier works, he always added the date of signing and never the date the work was made—another practice that gives rise to confusion and misunderstandings. And when he was asked to sign Passstücke (“Adaptives”) (which originally he had never signed), he occasionally took a subversive approach, adding his signature in such large and prominent writing that it became a dominant part of the work.

With all this, West was participating in an international discourse of the 1980s, which in light of the flood of images was rediscussing the meaning of individual and original production and—among other things with its debates on appropriation or simulacra—critically questioning or deconstructing the concept of the author and authenticity (cf. 2.1).

2.5.3 The reception of art as a subject of West’s works on paper and cardboard

West’s works on paper and cardboard again and again thematized the art world, its mechanisms and tools, the question of what art is and may accomplish, and what experiences, reflections, and dialogues it may trigger. Very often in such pieces from the 1980s one comes across people in various (at times spatially unclear) surroundings where they are viewing artworks, among them West’s own Passstücke (“Adaptives”), furniture, and sculptures. Into these settings he occasionally collaged the faces and bodies of other (famous) artists, and regularly included masterpieces from all eras of art history, in the form of photographs. Here artists and artworks alike create an atmosphere and are—for the people depicted as well as for the audience—“producers of states of being” due to their mere presence.

In these works, too, West wrote association-generating texts on the margin or in the picture. They have often been interpreted as titles, which is not necessarily wrong but only partly does them justice, as they are again intended to trigger reactions in the recipients, which constitute the crucial second (and always different) part of the impact and meaning of a work.

2.6 Picture walls, installations

West created entire surroundings not only in his works on paper but also de facto. By the early 1980s, he had already hung “picture walls” in Vienna’s Café Lukas with which he aimed to create “saturated fields of vision” and hence generate states of being via an artistic atmosphere while also initiating dialogues7. Later, ever-larger spatial ambiences were created, which he made both in the exhibition context and in public spaces and into which he also integrated sculptures and pieces of furniture.

2.6.1 Integration of works by other artists

Even in his early picture walls, West integrated works by fellow artists. Despite not yet being a respected or successful artist at that time, he was already moving in the innermost circles of the Viennese avant-garde, where he succeeded in convincing the “greats” to trade works with him. He mixed these acquisitions with his own works in his coffeehouse hangings. Later, he created this kind of walls for the exhibition context; in the same way, he created spatial ambiences in which he integrated the works of others alongside pictures, sculptures, and pieces of furniture. With increasing personal success, the names of the artists with whom he traded and the works he incorporated into his own pieces became more international and prominent. Yet once again, he was not interested in the artistic genius or name-dropping. Consequently, West presented works by less or unknown artists equally alongside his own works and those by big-name artists, including his neurodiverse friend Janc Szeniczei. When he later ran a large studio, he also frequently incorporated works by his assistants.

By hanging and positioning at times very different artistic creations closely alongside one another in his picture walls and spatial installations, West once again foiled the celebration of individual works and their authors and instead gave space to diverse intentions and means of expression.

2.7 Summary and conclusions

West saw his artworks not as autonomous objects for purely contemplative and reflective experience and deciphering, but rather as starting points and stimuli for reactions in the recipients, considering these essential and thus integral components of a work. In this way, the creations by an individual artist are relativized insofar as they are considered to be just one component of a process of experience and reception, which must be supplemented. Accordingly, the concept of the author is critically reflected on in his oeuvre and he himself adhered to a complex and at times broad concept of authenticity.

His approach to fakes was similarly complex, though that in no way means that he did not consider works falsely attributed to him as fakes, nor that he acknowledged them as his own works (cf. 3.9).

2.7.1 On West’s integration of fakes into his own creative work

In light of his integration of creations by a broad spectrum of other artists—regardless of their prestige or market value, and regardless of whether their concepts or style corresponded to his own or that of the others included—it becomes possible to understand how West was able to (deliberately or not) integrate works that had previously (or subsequently) been classified by himself and/or others as fakes. Just as works by other artists could interest him due to their different approach or often simply due to formal aspects, this, too, was possible with fakes.

To outsiders or rather people to whom West’s approach and way of thinking is alien, this may be difficult to comprehend. However, those who address the subject of his fakes responsibly and above all in a nuanced way, will understand it.

The AFW lists works whose authorship is questionable, but which West knowingly or unknowingly integrated into his oeuvre in a wide range of ways, under the category “Incorporations.” It should be noted that this only concerns a relatively small number of works, with West simultaneously making it very clear that he did not want to be associated with many other fakes (cf. 3.3 and 3.9).

In just a few cases did West also rework fakes and declare the results “Defakes.”

3. On the topic of fakes in the style of Franz West’s works

3.1 Point of departure: Documenting West’s oeuvre

Until the mid-1980s, only a small group of friends was aware of and appreciated Franz West’s work. It found no resonance to speak of in the art world, and, despite minor exhibitions at, among other places, the Viennese galleries nächst St. Stephan and Julius Hummel, the artist had no gallery representation in the strict sense. For this reason, it was almost exclusively he himself who saw to the sale of his works. Back then, he sold them to friends and acquaintances at extremely low prices without first documenting them or making any records of the sales. A systematic documentation of his oeuvre only began in 1985, when the then gallerist Peter Pakesch started representing him and did so until his gallery closed in 1993. Pakesch started a file that mainly registered the works produced from 1985 and took only initial steps toward recording the works created before then. This task was undertaken by the curator Eva Badura-Triska in 1992 when she was preparing the first retrospective of the artist (Franz West. Proforma, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien 20er Haus, 1996) and needed a collection of material to work with. Between 1992 and 1996, she visited a large number of collectors who had purchased works before 1985 and documented all the pieces by Franz West in each of these collections.

Together with the Pakesch file, her file formed the foundation of the Archiv Franz West’s (AFW’s) file of works, which with the artist’s consent and on the initiative and at the expense of David Zwirner (West’s gallerist between 1997 and 2000) was developed after the Proforma exhibition and incorporated into the AFW (a registered association) after its founding.

3.2 First indications of fakes

On numerous occasions, Badura-Triska went through and discussed with West the material she had collated in the run-up to the Proforma exhibition. In the process, she was able not only to gain a profound insight into the way he thought and worked, but also to gather lots of detailed information about the impulse for the creation of and intention behind individual works. West also told her the history (repeated here) of his sales before 1985.

The artist had a good memory and when shown again could remember well the vast majority of the early works he had sold. Admittedly, multiple times (also in writing) he declared—with some (feigned) modesty!—that he considered these works “bad,” but he never disputed their authenticity.

However, he became increasingly uncertain when prior to Proforma but chiefly afterward more and more works “surfaced” that he could not remember having created.

At first, no one thought of fakes, assuaging themselves that no one remembers everything. Even when to the art historians in West’s team some works seemed “somehow different,” at first no one considered that they might be fakes but rather saw them as unusual works, which are surely possible. Particularly because almost all of the “somewhat different” works that West could not remember came from a single collector who had purchased a large quantity of pieces in West’s early career. This is also why West himself unsuspectingly bought back some works from this collector, which after closer inspection and more intensive investigations, were later identified as fakes.

3.3 Notification of and investigations by the police

When the number of “newly surfaced” and “somehow different” works that West could not remember having made became suspiciously large and the artist became increasingly uncertain whether they indeed were from his hand, doubts were raised and investigations launched. Ultimately, West became convinced that fakes were in circulation. He hired a lawyer and filed a criminal complaint in 2005.

This led to comprehensive investigations by the police, the results of which were summarized in a report of which the AFW has a copy. It contains numerous clues and indications that fakes exist, despite the judge in the preliminary hearing assessing them to be insufficient for a criminal case to go to trial under public law.

3.4 Investigations by the Archiv Franz West (AFW)

In parallel with the criminal investigation being conducted by the police and in addition to West’s own assessments, the AFW conducted its own inquiries on the basis of other criteria to establish whether there were reasons to believe that fakes existed and were being sold. A study conducted by Eva Badura-Triska in collaboration with Andrea Überbacher (then employed by the AFW, thereafter at the Franz West Privatstiftung [FWPS], now retired) based on a large number of works was completed in 2007 that likewise called attention to a broad range of reasons for the existence of fakes.

West was very happy with this study and confirmed the following with his signature: “I have read Eva Badura-Triska’s text Zur Thematik der Fälschungen nach Werken von Franz West […] (‘On the Subject of Fakes of Works by Franz West […]’) and concur in every detail with the assertions made therein.

Specifically, I confirm the accuracy of the assertions in which Badura-Triska invokes statements made by myself.” (Vienna, October 20, 2007)

In 2009, this study was presented to a group of authorities on West—including Darsie Alexander (curator of the first retrospective on West in the USA [Baltimore], now senior deputy director and Susan & Elihu Rose chief curator of the Jewish Museum New York), Peter Noever (then director of the MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, now among other things a board member of the AFW), the gallerist Eva Presenhuber, Ines Turian (then Franz West’s assistant, now FWPS), and Andrea Überbacher-Kloiber (then AFW, thereafter FWPS, now retired). They were all in agreement with the paper’s conclusions and Franz West, who joined them toward the end of the meeting, was delighted by their support.

3.5 The suspicious collector and his version of the story

The source of the questionable works was obvious from the outset and the narrative accompanying the appearance of dubious works went as follows: a collector who is commonly known to have purchased a large number of works from Franz West at extremely low prices very early on in his career, had never made an orderly or structured record of his estate and therefore had no overview. “Chaos” reigned on his premises. According to the collector himself, he kept “finding” new pieces by Franz West there that he had long since forgotten about.

The conspicuously large number of “finds” put on the market by this one collector comprises predominantly small, portable pieces—specifically a special group of Passstücke (“Adaptives”) as well as early works on paper (from the second half of the 1970s and the early 1980s). These works are easy to integrate in a home and consequently ideal for the art market. By all accounts they were sold by the collector at prices below the then market prices for works by Franz West, which at the time had already risen considerably. The buyers were delighted to have found a bargain.

3.6. Authenticity sheets (ABC assessments)

Following the study by Eva Badura-Triska, from 2008 West signed “authenticity sheets” for numerous works. On these sheets the works were classified as A = genuine, B = fake, C = questionable, and West confirmed this with his signature.

The templates for the certificates were prepared by Eva Badura-Triska and Andrea Überbacher, whose assessments in almost every case accorded not only with one another but also with those of Franz West. In those rare cases where there was a divergence of opinion, no decision was made.

3.7 Decisions left untaken

Toward the end of his life West—in part due to his deteriorating health condition—only signed a few ABC assessments (cf. 3.6).

A great many of his works had already been evaluated by this point. What remained were mostly cases where it was especially difficult to reach a decision.

3.8. Accusations and defamation of West

Soon after Franz West and his team had started to deny the authenticity of certain works, the artist was accused of behaving capriciously in order to raise prices by creating a shortage on the market, as well as to gratuitously stain the reputations of certain individuals.

3.9 West’s published statement on the fakes

Understandably, the artist was upset, indeed hurt, by these accusations, and expressed this in a text that he published in the catalog of his last major exhibition (2009–2011, Museum Ludwig in Cologne, MADRE in Napes, Kunsthaus in Graz). In this “Nachschlag” (“postscript” ), he spoke explicitly about fakes and wrote: “[…] for some time, there have also been fakes of early graphic works and that obfuscates the matter. When this was pointed out to them, the owners declared me of unsound mind or made me out to be a cunning scammer—understandable, because their monetary loss is not inconsiderable. Perhaps they shouldn’t have speculated in the concoctions of such questionable artists after all.

With these fakes it is comparable to a journalist who wants to publish an article on me in an art magazine at the same time as this exhibition and thrust quotes under my nose that I never said and that don’t even sound like me. That is a distortion of who I am; it feels like undergoing facial surgery. […]

What I’m trying to say with all of this is that I feel like an object that is being treated by various entities in such a way as to fit into their concept. Despite the—in my opinion significant—differences from the originals, the fakes cannot be recognized as such by the authorities. The growing number is accepted; as an artist, one is apparently considered an imbecile or deranged.

The surge in the art market has led to the artist playing an ever-smaller role: not that of the artist but that of the eponym for products—a stuntman, as it were, for the ideas of curators, forgers, and photographers.”

With regard to a large group of questionable works with a sexual theme, he writes:

“With the fakes, it is especially mortifying that I may be taken for a horny devil, whereas with these sheets I considered myself to be a critic of the ‘new free sexuality’ of the 1970s, which, as the likes of Marcuse said, transformed eroticism into sexuality and living beings into butcher’s meat. The forger, however, is evidently attracted to the sight of any photo of a naked woman, whether fat or thin, young or old (a democratic trait desirable in anyone) and thus repeatedly accuses me of having his own character.

These sheets were [made] with a technique that corresponds to the skills of an advertising designer or scenographer—I now have just such a person as my assistant who explained this to me. They all come from the same source; further ones were also found there when a search warrant was executed, yet their seller was not punished because no action is taken against the production and sale of fakes. Things like that take the joy out of my life to a certain extent.”

Accordingly, he laments that the lack of prosecution by the courts “encourages the forgers to continue making and selling their interpretations of my early graphics on a large scale” and goes on to say: “Actually, the originals were executed sloppily, in a technique comparable to the way punk musicians handle musical instruments. They were a reaction to an earlier reading of Freud that, it seemed to me, pointed to an omnipresence of sexuality. I applied this understanding to the pornographic images and advertising illustrations in magazines, or to the pages of sewing catalogs, which brought me different—not sexual—stimulation. I did all this before my studies, during which I rather tended to abstain from graphic production. The statements I was making with these sheets were misunderstood by forgers, because sometimes I was also mocking advertising pages in a non-erotic way (an exception are advertisements for fine watches and lighters and cats, for which I have a weakness), which is understood by the forger to be affirmative fun—it cannot be denied that he has quite a portion of dullness.

One of the scammer’s employees, a scenographer, then produced very clumsy fakes—to prove that he cannot equal my (punk) graphic skills, we should believe that he was not capable of the refinement he attributed to me, but then he surprised us with skilled shading and with joke-like, droll interventions in advertising pages. Onto photos of advertising pages where children and housewife idylls were used as models, I often painted obscene, naked abdomens to offend producers and consumers alike, as I felt teased by their ‘world’ views, depictions of a sterile (asexual), ideal world. Back then, I still thought that the sexual assaults by adults that Freud’s patients so often complained of having suffered during childhood were figments of their imagination, but the current reports in the media about child porn clubs and human trafficking set me right. And I think that my pre-academy extremes (which should also class the Actionists as petty bourgeois gone wild) without prior understanding suit the information age as little as does Actionism. The target group of the League of German Girls (Bund deutscher Mädel), who have since mutated into dignified aunts, thankfully no longer exists, and searching passionately for new fields where I can be critically ‘setting the record straight’ (‘kritische Zurechtrückungen’)—as R. Priesnitz advised me to call these sheets—that’s just not my thing anymore.”

4. Authentication after Franz West’s death

4.1 Continued research

Established after Franz West’s death, the Authentication Board of the AFW has intensively inquired into the issue of forgeries. Among other things, the study by Eva Badura-Triska (cf. 3.4) was reviewed in detail and its continued validity as groundwork confirmed. Similarly, the authenticity sheets (ABC assessments, cf. 3.6) signed by West from 2008 were reappraised before being acknowledged as an important basis for the work of the Authentication Board.

Over the course of these repeated and further investigations, new indications and evidence have been and keep being found, which corroborate the conclusion that fakes are in circulation. Research in this regard is ongoing.

4.2. Authentication criteria, statements by the artist

Undoubtedly, identifying fakes is not always easy; indeed, the history of art is full of such examples. After all, there are better and worse fakes—also of works by Franz West—and for that reason, some are easier and some more difficult to identify.

An important tool is the comparison of doubtful works with unquestionable originals. Over time, however, with West a counterpole of clear fakes has also been established. Due to more and more compelling clues and evidence, this group has continued to grow and also provides valuable examples for comparison. Forgers make mistakes: They use the wrong materials, mix subjects and styles from different periods of an artist’s career, date the works incorrectly, and much more.

Among the various criteria that the AFW’s Authentication Board applies when making its decisions, the assessments of the artist himself are of course a crucial—though not the only—factor. It has always been important to the AFW to examine the question of works’ authenticity according to other criteria too (such as verified chains of provenance, aspects concerning the subject, style, or materials used, and much more). In the vast majority of cases, the results of the AFW’s additional investigations coincide with West’s own assessments.

Basically West had an excellent memory (cf. 3.2) when asked about his works from the period before 1985 (the period in which his work was not yet systematically documented, cf. 3.1). Concerning the works that he had no memory of, he also expressed himself very clearly as to whether they might be from his hand or definitely not.

Of course, there were also cases in which he was uncertain, for which reason he either refused to make a decision or may have later changed his mind. Here, it must be borne in mind that—like many other artists—he frequently doubted the quality of his own work, especially from his early career, which he occasionally declared bad across the board. This led to him being unsure both about the fakes he deemed “better” and those he considered “worse.”

In addition, West was concerned that he might be misremembering matters due to a phenomenon known as “Deckerinnerung” (screen memory). As a keen reader of Sigmund Freud, he repeatedly and explicitly used the term screen memory in connection with the fakes. He understood it in the sense of believing one can remember something simply because one has seen it so often—such as “recently surfaced” works that were shown to him again and again (cf. 3.2, 3.3, and 3.5)—even if at first he could not actually remember having created them. The question whether remembering a work might in fact be a screen memory is one that he posed on several occasions when asked about individual pieces.

With this in mind, West’s verbal and written classifications—all of which are precisely recorded in the AFW’s file along with their date and content—must be reevaluated. Not least, it must be taken into consideration at what time and with what degree of knowledge his decisions were taken. It should neither be forgotten that the systematic examination of the issue of fakes only began in 2005 nor that the criminal investigations undertaken from that time, as well as the simultaneous research conducted by the AFW (cf. 3.3 and 3.4), also gave the artist valuable points of reference when making his assessments (cf. 3.6), which in some cases prompted him to review his previous decisions.

The artist’s assessments (with classifications as A = genuine, B = fake, or C = questionable) signed from 2008—i.e., after the study was published—are cases where the artist’s judgment tallied with those based on the extensive research of the AFW, which at this point was already quite advanced (cf. 3.4). Consequently, they constitute an important foundation for the judgments passed by the AFW’s Authentication Board, even though they are carefully reconsidered in each case.

However, the Authentication Board of the AFW refuses as a matter of principle to share publicly any precise details about the criteria and justifications for each of the decisions it makes as there is a real fear they may be exploited for the production of new fakes.

4.3 Afterword

As a confirmation of authenticity has a significant effect on the market value of an artwork, owners of questionable works frequently urge the AFW to confirm Franz West’s authorship. Some people have even claimed that there are no fakes because the artist himself had been uncertain about some of the questionable works and at times changed his mind, or because he integrated some pieces in his own creative output. That these lines of argumentation are invalid has been elucidated here in detail (cf. 3.2–3.5 and 3.8–3.10). Regrettably, the notion that West made decisions capriciously and arbitrarily remains widespread. Like many institutions that deal with questions of authenticity, the AFW is confronted with the problem of some people (not least sellers) being interested not in the truth but in covering up the issue of fakes, which considering the facts described here is not only disrespectful but also irresponsible.

Statistically speaking, it should not be forgotten that the number of known works thus far classified as fakes or questionable is small compared to the total number of works by the artist: it corresponds to roughly 5% of all his works.

1The term “recipient” is used in this text to indicate a more active role for the audience than that of mere “viewer”: they “receive” the artwork in the sense of experiencing it, not just visually or intellectually, but with all senses and all other forms of perception like feeling or experiencing its atmosphere.

2The term Passstücke, coined in 1980 by Franz West’s poet friend Reinhard Priessnitz, was long translated as fitting pieces, an expression West always disliked. When in 1994 he consulted a dictionary in the British Library in London, he found the term adapter for Passtücke, which he immediately considered appropriate, not least because of the affinity of his Passstücke concept with that of the Bio-Adapter as developed by Oswald Wiener in his novel Die Verbesserung von Mitteleuropa (“The Improvement of Central Europe,” not yet translated into English). Reinhard Priessnitz had been a keen reader of Wiener’s writings. On the occasion of the exhibition Proforma (Museum moderner Kunst Wien, 1996), West decided on the term “Adaptives” as a translation for Passstücke.

3West explicitly used the term “Befindlichkeit,” though he emphasized that his understanding of the term was not identical to that of Martin Heidegger, who also used it. In Heidegger, the term has variously been translated into English as “disposedness,” “state of mind,” and “feeling.” In the context of Franz West, the translation “state of being” seems most fitting.

4These texts might be on sheets that were hung on the wall next to the sculpture, attached to the pedestals under the work, merely mentioned in the catalog, or elsewhere.

5On many occasions, West said that he had expressly called on the artist Allan Jones in London in order to get his autograph. He was given his signature at the door, only to immediately say goodbye and leave.

6Here it should be noted that West was not an artist who was true to principles, instead often leaving the option open to see and handle things differently. In this sense, he was acting on the authority of Wittgenstein among others: “Everything we see could also be otherwise. Everything we can describe at all could also be otherwise. There is no order of things a priori.” Ludwig Wittgenstein, TLP 5.634 (quoted by FW in his text to accompany Schöne Aussicht [Beautiful View], 1988, cf. Hans Ulrich Obrist, Ines Turian (eds.), FRANZ WEST SCHRIEB. Cologne 2011, p. 53.

7Cf. Eva Badura-Triska, Franz West als Sammler [Franz West as a collector], leaflet for the exhibition Sammlung West [Collection West], Raum Strohal Vienna 1994.

Translation: Maria Slater

Text: © Archiv Franz West, © Eva Badura-Triska

Images: © Archiv Franz West, © Estate Franz West

© 2022 Archiv Franz West

Impressum: Percept: Peter Noever / Design: Patrick Anthofer

contact